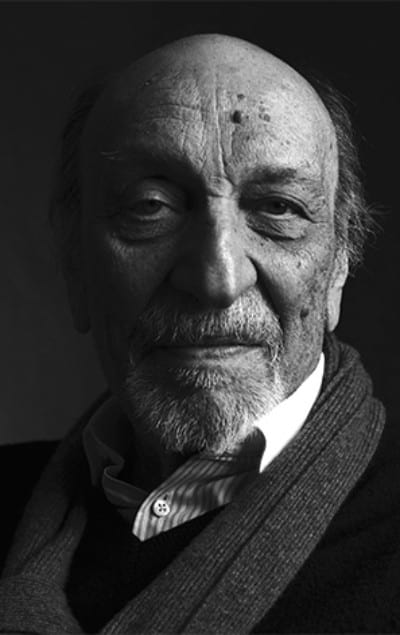

© Michael Somoroff

Milton Glaser

United States

"When it comes to paper, people associate authenticity with tactility."

Milton Glaser is probably the most famous graphic designer in the United States, well known for his I ♥ NY logo and his 1967 Bob Dylan poster. The young Glaser had studied with the painter Giorgio Morandi in Bologna. Back in the United States in 1954, he founded the Push Pin Studio with Seymour Chwast. In 1968, he created the New York Magazine with Clay Felker. In 1974, he opened his own agency, Milton Glaser, Inc., and since has produced spectacular designs, illustrations, publications, and posters. He has had the distinction of one-man-shows at the Museum of Modern Art and the Georges Pompidou Center. He is a member of the AGI (Alliance Graphique Internationale) since 1975. In 2009, he was the first graphic designer to receive the National Medal of the Arts award. Today, he is considered one of the most articulate spokesmen for the ethical practice of design.

Milton Glaser is always the tallest person in the room. Even when he sits down to talk to you, he looks like a giant. He dominates the situation with his size but also with his lofty ideas. A conversation with him about his work is likely to turn into a colloquy about the Nature of Reality or the State of the World. Listening to him, one gets the feeling that graphic design is a branch of philosophy.

Even though ninety percent of his work ends up in flatland – printed on paper – his design solutions are the result of a process of inquiry that explores a number of other dimensions – the historical, social, political, ethical, and cultural realms. “But there are no absolutes,” he says. “The realization that there is no definitive answer

to anything inspires me to create new forms.”

These days, the new forms Milton Glaser creates include the re-branding of the Kingdom of Bhutan – yes, Bhutan, the country in the Himalayas; posters for the final season of the television series Madmen; a book titled The Design of Dissent: Socially and Politically Driven Graphics; new packaging for the popular Brooklyn Brewery company; and a controversial campaign to rebrand the climate movement.

A philosopher in disguise, Milton Glaser is not a hermit. At the ripe age of 86, political engagement is still one

of his priorities.

Véronique Vienne

Interview

Véronique Vienne:

Printed matter is your life and your work, yet, over the phone, you told me that you had misgivings about the role of paper in the digital age. Can you explain?

Milton Glaser:

Yes, I have an axe to grind when it comes to paper, or, more specifically, when it comes to traditional books. We live in a time in history when we have to stop printing books that sit on shelves without being read. At best, books are read once and then put away, never to be seen again. In every house I know, including my own, there are thousands of books, rows of them, piles of them, simply occupying space.

Yet people love their books!

I am not saying that we have to burn books! What I am advocating is that we stop manufacturing most of them. In our day and age, we have other means to share knowledge with each other. We can do that electronically.

No, what I am saying is that books should be reinvented.

Books today must be works of art. They have to propose instant experiences, like paintings. You can look at the same painting all your life and never get tired of it: it can remain forever a source of delight, knowledge, and information. Likewise, books should not require you read them in order to enjoy them. Imagine a book you could leave open on a table, a book whose main function would be to be looked at, riffled through, played with, and it would never cease to satisfy you.

Can you give me an example?

By some strange coincidence, I was recently contacted by Joshua Prager, a distinguished author and journalist, who gave me an opportunity to test my theory. Originally, he wanted me to design a book of inspirational quotes, with one quote for each birthday, from one year all the way to a hundred years. I convinced him to transform the book into something that looks like a book but is part sculpture, part poetry, part anthology, and part artwork. I firmly believe that there is more to books than simply reading them.

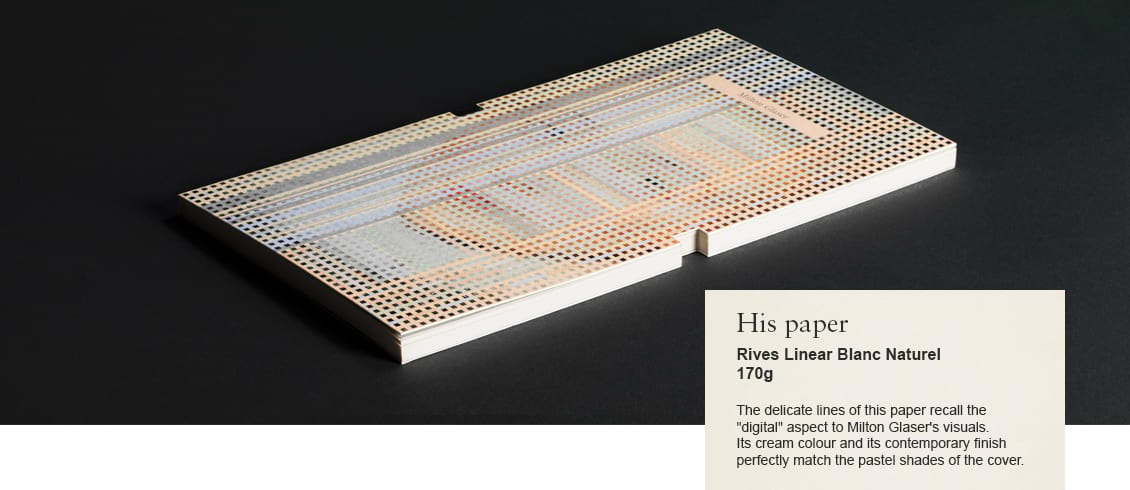

The book of quotes I created is at the convergence of narrative, form, and colors – with the pages darkening progressively both horizontally as well as vertically, going from light pastels to deep hues of blue and green as you leaf through it. I haven’t picked the paper yet. All I know is that it should be matte yet bright to enhance the subtle color variations.

Do you see the demise of traditional books as a positive outcome of the digital age?

We don’t know the consequences that all these changes will bring. Electronic devices are redefining our relationship with books, but also with friends, colleagues, and family. We might have to wait a long time to find out what influence the digital world has on our culture. All we know is that it has an influence – positive as well as negative!

Title - Post / Past

Title - Post / Past

Designer - Milton Glaser

Date published - 2014

Client - Hermitage Museum

Meanwhile, has digital design influenced your work?

Of course it has. One of my favorite posters is a digital image I create recently for the State Hermitage museum in Saint Petersburg. I was able to apply to the surface of the paper a succession of visual layers, about ten different layers. I didn’t proceed systematically, though. On the contrary, the computer allowed me to be playful and quirky. First I combined two images. Then I introduced a pattern on top of which I put a grid. Following my whims, I changed the grid before imposing a different pattern. Afterward I diminished the intensity of some of the colors while intensifying others. And so on.

My goal was to turn paper into something other than a flat surface. I wanted to push the boundaries of paper. I could have gone on forever. The real question in this digital game is how do you know when you are finished? When do you stop?

When did you stop?

The boundaries of the paper are the boundaries of the assignment. And then there are your needs, and the needs of your audience. But truth be told, I could have stopped earlier – or gone on for another ten layers.

Do you feel that it’s possible to go beyond the 2-D limitations of printed matter?

Let’s face it: increasingly, the difference between digital and analog is blurred. I am having more and more difficulty figuring out what’s what. Take my work, for instance. On top of the illustrations, the posters and the books, I have designed packaging, signage systems, logos, typefaces, magazines, interiors, and even products – yet I still can’t differentiate two-dimensional from three-dimensional design. To me, it’s all part of the same illusion. Basically, I don’t believe that there is an absolute reality out there. What we call reality is a representation composed inside our brain.

Yet, wouldn’t you agree that images printed on paper look more “real” than images viewed on the screen?

People associate authenticity – reality – with tactility. The perception is that if you can touch it, it’s real. That’s why stuff printed on rougher paper, paper that has a tangible texture, feels more “real” than stuff printed on smooth and glossy paper or stuff shown on a brilliant screen.

At the same time, the issue of authenticity is tricky. The beautifully printed, signed, authorized reproduction of my well-known Dylan poster is a lot less “authentic” than the poster included in the Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits album in 1967. Frankly, the newer poster looks a lot better and a lot brighter than the original one, printed on cheap paper. Yet, it is a lot less valuable because it’s not “the real thing.”

But for me, issues of tactility and authenticity have more to do with the hand than the paper itself.

What do you mean?

For me, the primary issue in the digital age is the relationship between the hand and the design process. Fewer and fewer designers draw by hand, and that’s a terrible loss. They no longer conceptualize alternative shapes because they are finding readymade images online. From my point of view, they are merely “finding” design solutions instead of creating them.

Yet Picasso used to say “I don’t search, I find.”

Picasso was drawing all the time! Drawing is not about creating a representation but about increasing attentiveness. When you draw something you become attentive. This is how you begin to make sense of the world. Drawing is about understanding. And since the hand is a modified brain – not merely an extension of the brain – drawing with the hand is drawing with a part of your brain.

For me, it is the most extraordinary encounter: a rough surface – paper – that accepts the trace of a writing tool. For a designer, it is the fundamental engagement.